+ JMJ +

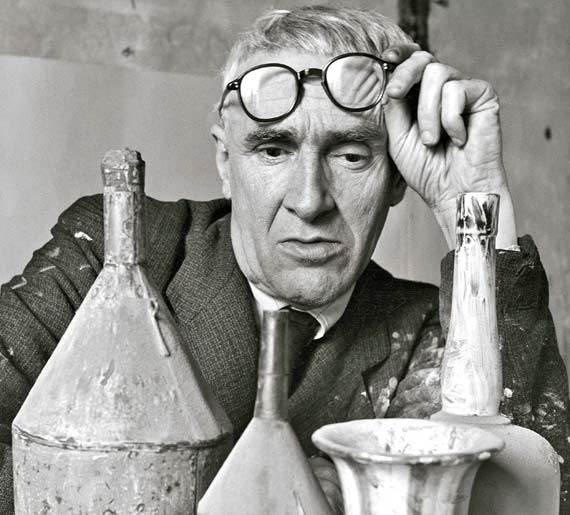

Giorgio Morandi (Italian, 1890–1964)

Photograph of Morandi in his studio in 1953

By Herbert List

[Source]

Still Life, 1916

Morandi first exhibited his work in 1914 in Bologna with the Futurist painters, and in 1918–19, he was associated with the Metaphysical school, a group that painted in a style developed by Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. Artists, who worked in the Metaphysical painting style, attempted to imbue everyday objects with a dreamlike atmosphere of mystery. [Source]

Morandi developed an intimate approach to art that,

directed by a highly refined formal sensibility, gave his quiet

landscapes and disarmingly simple still-life compositions a delicacy of

tone and extraordinary subtlety of design. [Source]

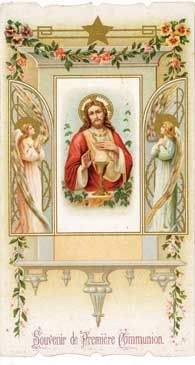

Still Life, 1938

Still Life, 1949

He taught drawing and printmaking for decades, first in elementary schools, then at the city’s art academy. He had many friends among Bolognese artists and intellectuals, who acknowledged and extolled his work. Like many artists in Italy before World War II, he had passive brushes with Fascist politics, though the degree of his commitment remains a matter of conjecture. What is not in doubt is his single-minded devotion to his work, and the path he traveled to develop it. [Source]

Still Life1955

Still Life1955

Oil on canvas

Photograph of Morandi in his studio in 1953

By Herbert List

[Source]

Giorgio Morandi is one of my favorite artists! I discovered his work while I was studying Painting and Drawing in Florence, Italy in the mid-80's. Here are some of his marvelous paintings.

Still Life, 1916

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Museum of Modern Art, New York

[Source]Museum of Modern Art, New York

Morandi’s still lifes are beautiful, they are so evidently shaped by self-restraint. Taken one by one, the paintings are close studies in rhythm and balance. [Source]

Flowers (Fiori), 1920

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

It is possible to think of (his) still

lifes ... as a meditation on time, art, isolation, self-preservation and

the ordinary mystery of all of that. [Source]

Morandi first exhibited his work in 1914 in Bologna with the Futurist painters, and in 1918–19, he was associated with the Metaphysical school, a group that painted in a style developed by Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. Artists, who worked in the Metaphysical painting style, attempted to imbue everyday objects with a dreamlike atmosphere of mystery. [Source]

Still Life, 1938

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Claudia Gian Ferrari Collection

Claudia Gian Ferrari Collection

Still Life, 1938

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Museum of Modern Art, New York

[Source]

His gentle, lyrical colours are subdued and limited to clay-toned whites, drab greens, and umber browns, with occasional highlights of terra-cotta. [Source]

The White Road, 1939

(La Strada Bianca)

Still Life, 1943

Still Life, 1943

Still Life, 1947

Still Life1947 - 1948

His gentle, lyrical colours are subdued and limited to clay-toned whites, drab greens, and umber browns, with occasional highlights of terra-cotta. [Source]

The White Road, 1939

(La Strada Bianca)

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Private Collection

[Source] Private Collection

Morandi’s paintings of bottles and jars convey a mood of contemplative repose reminiscent of the work of Piero della Francesca, an Italian Renaissance artist whom he admired. [Source]

Still Life, 1943

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

Still Life, 1943

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Hirshhorn Museum of Sculpture Garden

Washington, DC

[Source]

Morandi comes with his own personal mystery, or myth, depending on

what you hear. There seem to be two stories, the first of which — the

life of St. Giorgio the Hermit — is the more popular. [Source]

Still Life, 1947

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

[Source]Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

Still Life1947 - 1948

Oil on Canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

It is the

tale of a deeply reclusive Italian artist who lives his whole life in a

single apartment, from which he rarely goes far. Though he teaches

printmaking in the local art school, he sees almost no one socially. He

rarely travels, is unaware of public events around him, knows little of

new art elsewhere. Despite scant recognition of his art, he doggedly

paints away in a tiny at-home studio to the end of his days. [Source]

Still Life1948 - 1949

Oil on canvas

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

Still Life, 1948 - 1949

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

Then there is a second story. In this one a shy but cosmopolitan painter

socializes regularly with fellow artists and keeps up, through books

and magazines, with art developments in the larger world. He travels

extensively within his homeland and is alert to events, political and

otherwise, there. His work attracts an international following.

Genuinely retiring by nature, he uses his reputation as a recluse to

pick and choose his company and to reserve his energies for art. [Source]

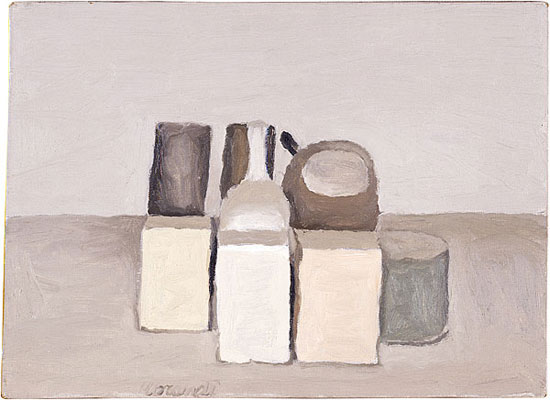

Still Life, 1949

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

[Source]

Details from both stories dovetail in the life of the real Morandi. He

was born in Bologna, in northern Italy, into bourgeois comfort. He

studied art in the city and never moved from his family’s apartment,

which he shared with three unmarried sisters. There he had a small

bedroom, and adjoining it, an even smaller studio. [Source]

Still Life, 1949

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Museum of Modern Art, New York

[Source]Museum of Modern Art, New York

He taught drawing and printmaking for decades, first in elementary schools, then at the city’s art academy. He had many friends among Bolognese artists and intellectuals, who acknowledged and extolled his work. Like many artists in Italy before World War II, he had passive brushes with Fascist politics, though the degree of his commitment remains a matter of conjecture. What is not in doubt is his single-minded devotion to his work, and the path he traveled to develop it. [Source]

Still Life1951

Still Life, 1951

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Museo Morandi, Bologna, Italy

[Source]

From his student

years he knew and revered the art of Cézanne; the earliest paintings at

the Met attest to this. From 1913 comes a Mont Sainte-Victoire-ish

landscape done at his family’s summer home; and from two years later, a

variation on Cézanne’s “Five Bathers,” but with nudes that look as

boneless, slippery, and compressed as sardines packed in oil.

Thereafter, apart from a few youthful self-portraits — two are in the

show — Morandi avoided the human figure. [Source]

Still Life1952

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Yet he was looking at

lots of figures, all the time. In 1910 he made his first trip to

Florence and saw Giotto’s paintings, with their firm, blocklike,

feet-on-the-ground bodies anchored in space. In Rome came another

revelation: the fleshly miracles of Caravaggio.

And at some point, somewhere, possibly in Urbino, he began a long

relationship with the sun-bleached bodies and buildings of Piero della

Francesca. [Source]

Still Life1953

Oil on canvas

[Source]

From all of these artists, Morandi learned something. From Giotto

and Caravaggio he learned how to create weight in painting. From Piero

he learned about light and its drama. From Cézanne he took two things.

One was the idea of nature as personal artifice, something you observed

but then made up. The other was a piece of cautionary advice: “The

grandiose grows tiresome.” [Source]

Still Life1955

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

Morandi is never grandiose, though he can be grand. And despite his

repetition of themes, he is never wearing. I found myself waking up

rather than winding down as I walked through the show. [Source]

Still Lifec. 1955

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

Still Life1955

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

[Source]National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

He also included Corot and Chardin in this aesthetic start-up kit.

And he took careful notice of his contemporaries. He checked out the

Futurists. After meeting Carlo Carrà and Giorgio di Chirico, he briefly

aligned himself with the movement or style called Pittura Metafisica, to

which he contributed a few immaculately spacy still lifes. [Source]

Still Life, 1956

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Yale University Art Gallery

Still Life, 1956

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Source]

But metaphysics, to the extent that it involved a belief or a program, was never of interest to him in art. And in the 1920s he moved on to painterly realism. The two self-portraits — virtually identical, expressionless, slightly hangdog — date from this time, as do landscapes dominated by houses with Piero-style light-washed walls. [Source]

Still Life, 1956

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

[Sold for $1.2 million at Bologna’s Galleria d’Arte Maggiore.]

[Source][Sold for $1.2 million at Bologna’s Galleria d’Arte Maggiore.]

And the production of still lifes began in earnest, the first of

which were thickly brushed and densely populated tableaus. Filled to the

edges with bristling forms — skinny bottles, pots with sticking-out

handles — they are done in nougat beiges and chocolate browns, bread and

earth colors, interrupted by patches of mineral-red and cobalt blue. [Source]

Still Life1957

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sydney, Australia

Sydney, Australia

[Source]

His repertory of studio props, salvaged from the family kitchen or

bought secondhand, was more or less in place. It encompassed carafes of

various sizes, jars, teapots, Ovaltine boxes and vases, with and without

flowers. Some of these containers he customized, touched up with paint

or covered with paper, to make them look generic, to call attention to

their shape and mass. [Source]

Still Life1957

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Princeton university Art Museum

[Source]

Still Life1957

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Musée Jenisch, Vevey, Switzerland

Musée Jenisch, Vevey, Switzerland

Certain items came and went. Strange clocks were prominent for a

while, then disappeared. In the early 1940s there was a sudden infusion

of seashells. With their irregular shapes, spectral colors and

dangerous-looking protrusions, they introduced a disturbing, aggressive

organism into Morandi’s pictorial world. It is surely no coincidence

that the shells appear in paintings done at a time in World War II when

Bologna was being bombed. [Source]

But Morandi’s still lifes from all periods can be visually unsettled

and psychologically fraught. In a series from 1941, arrangements of

bottles and vases, painted in tones of white and light gray and arrayed

processionally across the canvas, suggest the serene, if icy, facade of a

Doric temple, but with columns so closely placed as to prevent

admission. [Source]

Still Life1961

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Museo Morandi, Bologna, Italy

Museo Morandi, Bologna, Italy

[Source]

Later, in the 1950s, objects grow fewer and smaller in scale and

tend to be centrally placed in stretches of empty space, an effect a

little reminiscent of abstract, “cosmic” Wagner productions of the time.

In some cases we view the arrangements at eye level, but more often

from slightly above. From this commanding God’s-eye perspective, the

objects look slight, squat and vulnerable, like figures awkwardly

pressing together for a snapshot, or huddling under a searchlight. [Source]

In

Morandi's still-life paintings, the artist used the same objects

repeatedly; the subject was secondary to the manner of representation.

After 1950, his style became increasingly abstract. In this painting,

the objects are grouped together in the centre of the composition, as if

in self-protection, and are painted with a nervous, quivering line.

Morandi is dealing primarily with shape, space and colour, and seems to

avoid all hint of symbolism or narrative. However, his choice of subject

matter and manner of presentation suggest qualities of modesty,

reflection and silence. [Source]

![Natura Morta [Still Life]](http://www.nationalgalleries.org/media/38/collection/GMA%20906.jpg)

Still Life1962

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

National Galleries Scotland

National Galleries Scotland

[Source]

Although Morandi rejected the idea of abstraction in his art, that

was the direction it was heading. The last oil-on-canvas still lifes are

basically composed of blocks and cylinders — are these containers? what

could they contain? — and snarled-up biomorphic forms merging into

other forms. And in watercolor painting, which became his late preferred

medium, solids become mere stains soaked into atmosphere. [Source]

Landscape, 1962

Oil on canvas

Giorgio Morandi

Museo Morandi, Bologna, Italy

[Source]

By then, Morandi had achieved international fame, both for his

paintings and for his extraordinary prints, which are too little sampled

in the show, organized by the Met and the Museo d’Arte Moderna of

Bologna, with Maria Cristina Bandera, director of the Roberto Longhi

Foundation in Florence, and Renato Miracco, director of the Italian

Cultural Institute in New York, as curators. [Source]

You might ask other artist-poets this question: Joseph Albers, say, or Paul Klee or Agnes Martin or a New York artist I know who sits down at his apartment desk for two hours every day — only two, but always two — to embroider small squares of raw canvas with abstract patterns in silk thread. The work is close, slow and painstaking, done stitch by stitch, row by row — letter by letter, line by line — in calligraphic loops and tufts. An inch of embroidery, approximately the size of a sonnet quatrain, takes months to complete. [Source]

His hand had lost steadiness; his eyesight was, perhaps, failing. But he didn’t rest. He kept painting. Why? [Source]

... the work goes on. Because it is controllable reality. It is a

form of thinking that frees up thought. It is time-consuming, but

time-slowing, isolating but self-fulfilling. It is a part of life, but

also a metaphor for how life should be: with everything in place, every

pattern clear, every rhyme exact, every goal near. [Source]

(Text excerpts from New York Times article written by Holland Cotter.)

No comments:

Post a Comment